AI in Oral Cancer Diagnosis in India: Insights from Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal (Part-5)

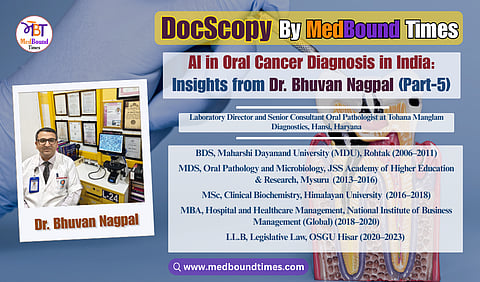

In an era where early diagnosis can mean the difference between timely intervention and advanced disease, oral pathology plays a quietly critical role in dentistry and cancer prevention. MedBound Times spoke with Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal, a distinguished oral and maxillofacial pathologist, clinical biochemist, and medico-legal consultant whose work spans diagnostics, research, public health, and healthcare law. With an extensive academic background that includes BDS (MDU, Rohtak), MDS (JSS, Mysuru), PGT in Head and Neck Oral Pathology, MSc, MBA, PGDMLS, LL.B, Ph.D (Honorary), and multiple professional certifications including CLQMS and FPFA (USA), Dr. Nagpal exemplifies lifelong learning and academic rigor, positioning himself at the intersection of precision diagnostics and multidisciplinary healthcare practice.

Currently serving as the Director of Tohana Manglam Diagnostics and a Business Partner at Manglam Diagnostics, Hansi, Haryana, Dr. Nagpal’s clinical focus lies in histopathological evaluation, early identification of oral potentially malignant disorders, and comprehensive head and neck diagnostics. Beyond clinical practice, he is the Founder and President of the Practicing Oral Pathologists and Microbiologists Association (POPMA) and the driving force behind the Centre for Oral Pathology and Maxillofacial Diagnostics (COPMD), India’s first dedicated chain of oral pathology diagnostic centres, aimed at strengthening the visibility and impact of oral pathology nationwide.

In this MedBound Times interview series, conducted by Dr. Akriti Mishra, Dr. Nagpal discusses the future of oral cancer care, including the role of AI in oral pathology and emerging diagnostic technologies that can improve access and accuracy across India.

Dr. Akriti : With emerging AI tools, how do you envision the future of oral cancer diagnostics in India?

Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal : The future of oral cancer diagnostics in India with AI is poised to be transformative, especially in a country where access disparities and high risk-factor prevalence remain major challenges. AI can become the silent partner in expanding early detection, improving accuracy, and optimizing healthcare delivery. I envision it as a game-changer that will complement our work and vastly improve early detection, especially in resource-limited settings. Here’s how I see it unfolding:

AI-Powered Screening: One of the biggest challenges in India is the shortage of specialists to screen the vast population. AI can help bridge this gap. We are already seeing experiments where an AI algorithm is trained to analyze photographs of the oral cavity to detect suspicious lesions. Imagine a basic health worker or even a person at home taking a simple smartphone photo of a mouth lesion and AI could analyze it for patterns (color, texture, shape) that suggest it’s malignant or premalignant. In fact, studies have been done using AI to identify precancerous lesions from photos with promising accuracy. This means in the future, a mobile app could triage patients: “Green – looks normal, check again later” or “Red – looks suspicious, see a doctor now.” Such a tool could empower even remote villages to do preliminary screening. I see mobile vans or primary health centers using an AI-based camera that flags lesions, making mass screening feasible.

Enhanced Diagnostic Aids in Clinics: Devices like the OralScan that we discussed already use AI-like software. OralScan, for example, is a handheld device that uses optical imaging and a software algorithm to highlight abnormal tissue and guide the optimal biopsy site. This is essentially AI assisting the clinician to not miss lesions and to sample the most representative area. Going forward, more such devices will become available and affordable, maybe an attachment to an intraoral camera that many dentists have, which can show through fluorescence or other modalities where the suspicious areas are. AI can improve the sensitivity of these devices, reducing false negatives.

AI in Pathology (Digital Pathology): On the diagnostic side in the lab, I anticipate a shift to digital pathology where biopsy slides can be scanned and analyzed by AI algorithms. AI can help detect cancer cells on slides, quantify the degree of dysplasia, and even find tiny foci of invasion that a human might overlook. This doesn’t replace the pathologist, but it acts as a second pair of eyes, improving accuracy and speed. It’s like having a diligent assistant that marks areas on a slide for the pathologist to review closely. This could especially help when there’s a high volume of cases. In places where a specialist isn’t available on site, a slide could be scanned and uploaded, an AI gives a preliminary read, and then a remote oral pathologist confirms; thus facilitating tele-pathology services across India.

Predictive Analytics and Risk Assessment: AI can also crunch large datasets to predict which lesions are likely to turn malignant. For example, by analyzing thousands of patient records, AI might help create a risk model: a patient inputs data about age, habits, and maybe a photo of their lesion, and the AI could estimate the risk level and recommend urgency of intervention. This personalized risk assessment can optimize resource use by ensuring those who need quick treatment get flagged.

Integration with Telemedicine: I foresee AI tools integrated into tele-dentistry platforms. Suppose a patient in a rural area is concerned about something in their mouth and they use an app to take pictures, answer a few questions (like “how long have you had it? do you smoke?”), the AI analyzes the info and then connects the patient to a dentist via teleconsultation if needed. The AI might even generate a preliminary report (“lesion likely benign vs suspicious”) for the dentist, who can then advise properly. This makes expert guidance reachable to remote corners without physical travel, aside from when a definitive treatment or biopsy is needed.

Expediting Screening Programs: On a larger scale, if the government or health NGOs deploy an AI-based screening program, it can massively scale up our reach. For instance, screening all tobacco users in a district by having health workers use an AI app and those that come up positive or suspicious would be the ones that oral surgeons or pathologists then see in person. This focus means specialists’ time is better utilized, and we catch more cancers early. Considering less than 1% get screened currently, AI could help raise that percentage by making screening easier and more automated.

Continuous Learning and Adaptation: One of the beauties of AI is that it learns and improves as it gets more data. Over time, as AI systems gather more examples of Indian patients’ lesions and pathology, they’ll become very adept at recognizing even subtle patterns that indicate early cancer. They might even discover new patterns that humans haven’t formally described (like particular color hues or network patterns in oral mucosa that correlate with dysplasia). This can feed back into our scientific understanding.

Affordability and Accessibility: AI-based tools, especially software, can be relatively low-cost once developed, because you don’t need an expensive consumable each time. All you need is a smartphone or a computer, which are increasingly common. This means even lower-income settings could potentially utilize AI tools. For example, an app for basic screening might be free or cheap, supported by public health agencies. The Make-in-India approach to devices like OralScan also aims to keep costs lower (I recall OralScan is priced at some lakhs of rupees which is a one-time cost for a clinic). As demand grows, costs usually come down further.

AI in Research: AI will also help in research for oral cancer, like analyzing genomic data to find patterns or analyzing demographic data to identify hotspots and trends. This indirectly improves diagnostics because we might find, say, new biomarkers that AI helped to pinpoint, which we can then test for in the lab.

Of course, there are challenges. AI is only as good as the data it’s trained on. We need to ensure our AI tools are trained on diverse Indian population data to be truly effective (lesions can look different on different oral mucosal pigmentations, etc.). We also have to integrate these tools into the healthcare workflow in a way that practitioners trust and use them. There might be initial skepticism, but as we demonstrate their utility, I believe adoption will grow.

In the next decade, I envision a scenario where AI is an assistant at every step: from a village health worker’s initial screening of a patient’s mouth, to the pathologist’s slide analysis, to the oncologist’s treatment planning (AI can even help suggest treatment based on best evidence). This will not replace the need for skilled doctors and pathologists, but it will make their work more effective and far-reaching. Ultimately, the dream outcome is that no potential oral cancer goes unnoticed even in far-flung areas because an AI alert will ensure the patient gets flagged and connected to care. This could significantly cut down the number of late-stage presentations and improve survival rates in India.

Dr. Akriti : Are there ongoing research gaps in oral pathology or oral oncology in India that you believe need urgent attention?

Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal : Yes, absolutely. There are several research gaps and needs in oral pathology/oncology in India that require urgent attention:

Early Detection Strategies and Implementation Research: One major gap is figuring out the best ways to implement early detection on a wide scale in our population. We know what to do in principle (screen high-risk people, etc.), but there’s a need for research on how to do this effectively in India’s diverse settings. We need studies on different screening models, for example, can trained community health officers or rural dentists perform effective oral cancer screening, and what’s the best training module for them? How do we increase uptake? Perhaps comparing outcomes in regions with active screening vs. those without. Right now, as earlier mentioned, screening coverage is dismal (under 1%). Research could identify the barriers in more detail (we have some data on awareness being low, etc.) and test interventions to improve this. For instance, a trial where one district gets an intensive awareness + screening program and a similar district doesn’t, and then compare oral cancer stage at diagnosis in both. This kind of operational research can convince policymakers to adopt national screening more vigorously if effective.

Biology of Oral Cancer in Indian Context: On the pathology side, we need more research into the molecular and genetic characteristics of oral cancers in Indian patients. Our population has a high incidence, and unique exposures (like areca nut) that might cause different molecular changes. Are there genetic mutations or biomarkers more prevalent in our oral cancer patients? For example, does the profile of HPV-associated oral/oropharyngeal cancers in India differ from the West? Research could focus on sequencing tumors from Indian cohorts. This could reveal targets for therapy or early detection (e.g., a salivary marker specific to our population). Also, conditions like oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF), which is common here due to betel nut, have a risk of malignant transformation. We need studies on which biomarkers or clinical features predict which OSMF cases will turn cancerous. That’s a gap because a lot of data we reference comes from Western studies, which might not perfectly apply here.

Premalignant Lesions and Progression: Relatedly, research on oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs), which includes leukoplakia, erythroplakia, OSMF, lichen planus, is needed to better stratify risk. For example, two people have leukoplakia; one progresses to cancer, the other doesn’t. Why? Are there differences at the molecular level? Some work is ongoing, but we need robust longitudinal studies in India following patients with these lesions to identify key predictors of progression. This will help in management, i.e., deciding whom to treat aggressively vs monitor. We also need to test chemopreventive agents (like is there a vitamin or medication that can reduce progression in high-risk lesions?) specifically in our population.

Epidemiological and Regional Data: India is vast, and oral cancer patterns can vary regionally. There’s a gap in having comprehensive data, although our cancer registries are improving. For instance, a recent study highlighted geographic disparities in oral cancer survival within India (patients in some regions had worse outcomes than others). We need to understand why: is it access to care or is it differences in tumor biology or stage at diagnosis? Research should delve into these disparities so that targeted interventions can be made (like improving facilities in certain regions, or specialized training where needed). Essentially, epidemiological research that continuously monitors incidence, survival, and risk factor prevalence is crucial. It can also reveal emerging trends, e.g., if tobacco habits change, does the demographic of oral cancer change?

Public Health and Behavioral Research: Another gap is research on effective behavior change strategies for risk habits. We know tobacco and areca nut are the main culprits, but what are the best ways to get people to quit or not start? This overlaps with psychology and sociology. Trials of different cessation interventions (maybe use of mobile messaging for quitting, or community peer support groups, etc.) specifically targeted at chewers and smokers in India could yield strategies that work. Reducing incidence via prevention is as important as better treatment.

Technology and Diagnostic Research: As we discussed AI and other diagnostics, we need Indian-led research on these fronts. For example, developing a robust AI algorithm for oral lesion detection requires gathering a large dataset of images from Indian patients (with different lighting, camera types, etc.), and that’s a research project in itself. Likewise, evaluating new diagnostic adjuncts (like salivary biomarkers or fluorescent devices) in the Indian field setting is needed. It’s one thing for a device to work in a lab, another to prove it helps in community screening. Research can test these tools in the real world, e.g., does using a brush biopsy or salivary DNA test in addition to a visual exam improve early detection in a village health camp? Such studies would guide us on which innovations to adopt.

Treatment-Oriented Research (Clinical Trials): While pathology is my domain, I must mention that in oral oncology broadly, there’s a need for more clinical trials focused on oral cancer patients in India. Most patients here present late; we should research the best treatment protocols for advanced cases given our resource constraints. Also, reconstructive techniques, quality of life studies post-surgery, etc., are very relevant for Indian patients and deserve attention. We also have to explore cost-effective therapies, perhaps repurposing inexpensive medicines for adjunct treatment (there have been ideas like using metformin, etc., which could be tested).

Multidisciplinary and Translational Research: We have gaps in translating findings from lab to clinic. For example, if a molecular marker is discovered that signals early cancer, turning that into a readily available test (like a simple kit that a lab in a tier-2 city can run) requires applied research. Encouraging collaborations between oral pathologists, geneticists, and biotechnologists is necessary to develop such tests or treatments.

Training and Manpower Research: We should also research the manpower and training aspect. How many oral pathologists or oncology-trained dentists do we need per population? Are our current training programs producing graduates with the skill set to perform as needed (for example, can every new oral pathologist sign out biopsies confidently, or do they need additional mentorship)? Studies or surveys can identify gaps in skills or numbers, which can inform educational reforms.

To boil it down, the pressing research needs are: How to detect earlier, how to prevent better, and how to understand our desi profile of the disease better. India has a high burden, so solutions that work for us could also help other countries with similar problems. But we must invest in this research.

The encouraging part is that I see more interest and funding coming for oral cancer research now than a decade ago – likely because the magnitude of the problem is being recognized at policy levels. We have capable scientists; we just need to focus efforts on these key gaps. If we tackle these research questions, the knowledge gained will pave the way for significant improvements in how we manage oral health and cancer in the coming years.

In this part, the discussion shifts toward the future of cancer care, especially with AI-enabled diagnostic tools that can improve diagnostic precision and strengthen early oral cancer detection across India. The conversation also draws attention to key research gaps that demand urgent focus to advance oral cancer care in the country. Moving ahead to the last section of this in-depth interview, Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal reflects on the collective ethical responsibility of dentists and oral pathologists in patient counseling, timely diagnosis, and diligent follow-up to ensure continuity of care. He also addresses aspiring dentists and young professionals, sharing practical guidance for those drawn to oral pathology and research—highlighting the importance of professional integrity, diagnostic vigilance, mentorship, and a commitment to lifelong learning.