Oral Cancer Diagnosis and Prevention: Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal on Risk Factors and Early Detection (Part-3)

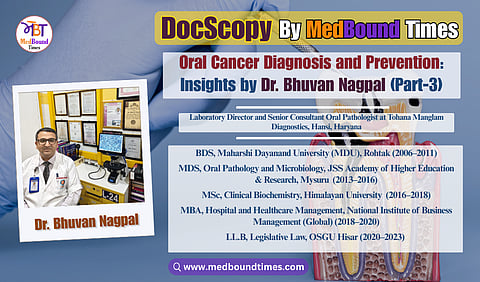

In an era where early diagnosis can mean the difference between timely intervention and advanced disease, oral pathology plays a quietly critical role in dentistry and cancer prevention. MedBound Times spoke with Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal, a distinguished oral and maxillofacial pathologist, clinical biochemist, and medico-legal consultant whose work spans diagnostics, research, public health, and healthcare law. With an extensive academic background that includes BDS (MDU, Rohtak), MDS (JSS, Mysuru), PGT in Head and Neck Oral Pathology, MSc, MBA, PGDMLS, LL.B, Ph.D (Honorary), and multiple professional certifications including CLQMS and FPFA (USA), Dr. Nagpal exemplifies lifelong learning and academic rigor, positioning himself at the intersection of precision diagnostics and multidisciplinary healthcare practice.

Currently serving as the Director of Tohana Manglam Diagnostics and a Business Partner at Manglam Diagnostics, Hansi, Haryana, Dr. Nagpal’s clinical focus lies in histopathological evaluation, early identification of oral potentially malignant disorders, and comprehensive head and neck diagnostics. Beyond clinical practice, he is the Founder and President of the Practicing Oral Pathologists and Microbiologists Association (POPMA) and the driving force behind the Centre for Oral Pathology and Maxillofacial Diagnostics (COPMD), India’s first dedicated chain of oral pathology diagnostic centres, aimed at strengthening the visibility and impact of oral pathology nationwide.

In this DocScopy interview, conducted by Dr. Akriti Mishra, Dr. Nagpal outlines diagnostic methods including biopsy, histopathology, and clinical correlation to differentiate benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. He also shares evidence-based preventive strategies, focusing on tobacco cessation, early referral, and regular dental check-ups to reduce oral cancer risk.

Dr. Akriti Mishra: What diagnostic techniques and investigations (biopsy, histopathology, imaging, molecular diagnostics) do you rely on most and how accessible are these in typical dental settings across India?

Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal: The cornerstone of diagnosing any suspicious oral lesion is biopsy followed by histopathological examination. This remains the most reliable and widely used diagnostic method in my practice. Whether a patient presents with a persistent ulcer, red or white patch, or unusual oral mass, the first step is to perform a biopsy, either excisional (complete removal if the lesion is small) or incisional (sampling a representative portion). The tissue is then examined under a microscope to determine if it is benign, dysplastic (pre-malignant), or malignant. Histopathology is considered the gold standard for oral cancer diagnosis. No matter what other fancy tools we have, we still confirm things by looking at the cells and tissue architecture microscopically. As an oral pathologist, I spend a large part of my time analyzing these biopsy slides.

In terms of accessibility:

Biopsy and histopathology: These services are readily available in most cities and major medical institutions. Dental colleges often have Oral Pathology departments that process biopsies, and there are numerous private oral pathology labs across India. While smaller towns or rural clinics may not have on-site lab facilities, dentists can still perform the biopsy and send the tissue to a laboratory. However, some general practitioners may lack the training or confidence to perform biopsies, and patient hesitation due to cost or fear can also be a barrier. But purely in terms of availability, any dentist can take a biopsy and courier it to a pathologist. The turnaround time is usually a few days for results. So, biopsy/histopathology is widely accessible in theory, though in practice there may be logistical delays in outlying areas (sending samples to city labs, etc.). One of my personal initiatives, through COPMD, is to create a referral network that helps remote clinics connect efficiently with diagnostic centers for timely analysis and reporting.

Imaging techniques: Once we have a confirmed diagnosis (or if we strongly suspect one clinically), imaging helps to assess the extent of the lesion. In a dental setting, the commonly accessible imaging would be things like X-rays – for example, an OPG (panoramic dental X-ray) can show if bone is involved under an ulcer, or an intraoral radiograph might show a hidden tumor affecting bone. Many dental clinics have X-ray units. For more advanced imaging like Ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI, typically the patient would be referred to a bigger center or hospital. These imaging modalities are crucial for staging an oral cancer (seeing how deep it is, whether lymph nodes are involved, etc.), but they are not usually found within a small dental clinic. They are accessible in the sense that almost every district has some radiology center now – CT and MRI machines are in all major hospitals. The issue is often the cost and the coordination – a patient with suspicion of cancer found by a dentist will usually be sent to an oncology center for those scans. So, while I rely on imaging for comprehensive diagnosis and treatment planning, I wouldn’t say advanced imaging is available at every dental office. It’s available at tertiary care centers. On a positive note, even some state governments have programs to provide free or subsidized scans for cancer workup in government hospitals, improving accessibility for those who need it.

Molecular diagnostics and advanced tools: These include things like testing for specific biomarkers (for example, HPV testing in throat/oropharyngeal cancers, or genomic assays), immunohistochemistry (IHC) to characterize tumors, and even emerging saliva-based or blood-based tests. In a typical dental practice, these are not routine. They are mostly available at specialized labs or research centers. For instance, if I suspect a lesion might be related to a virus (like an HPV-associated lesion), I might recommend PCR or IHC testing for that virus – but the sample would be sent to a specialized lab. Molecular tests can also include checking for gene mutations or using FISH (fluorescence in-situ hybridization) to see if certain genes are present; these are usually done in academic or large cancer hospitals rather than small clinics. So accessibility is limited in general practice – they’re used on a referral basis. The cost can also be a barrier; these tests are often expensive, so we reserve them for when they will really change management.

Adjunctive diagnostic aids: Some dental practices use brush biopsies (also called exfoliative cytology, where you use a brush to collect cells from a lesion for analysis), which is less invasive than a scalpel biopsy and can be done chairside. It’s a useful screening tool but if it’s positive or suspicious, a conventional biopsy is still needed. Some dentists use it if patients are very reluctant for a biopsy. There is also toluidine blue staining, which is a special dye that can be applied to highlight potentially dysplastic areas. Some autofluorescence devices (like VELscope) shine a light to detect abnormal tissue. These tools can help in a clinic to decide if a lesion is suspicious. However, their availability is mostly in upscale clinics or institutions; the average dental clinic in India likely doesn’t have a VELscope or similar device. A promising development is the introduction of tools like OralScan, a handheld oral cancer screening device developed in India. It integrates AI-based analysis to aid early detection and guide biopsies, which is a major step forward in improving diagnostic access in general practice settings. At the grassroots level, particularly in rural India, screening is often limited to visual inspection with a torch. While this method is better than no screening, it lacks sensitivity for detecting subtle pre-malignant changes. Expanding access to training and diagnostic tools for frontline healthcare workers is therefore a pressing need.

It’s also important to mention that currently, in many primary health setups, screening is done by simple visual examination with a torchlight, especially in rural camps. That basic method can miss early subtle lesions, which is why we want to get more training and better tools out there.

In summary, the main diagnostic method I rely on is biopsy with histopathology, and that is considered the definitive test available fairly broadly (through labs). Imaging (X-ray, CT, MRI) is used for assessing the spread and is accessible via referral to hospitals. Molecular and advanced diagnostics are used selectively and are mostly accessible in bigger cities or specialized centers, not every dental clinic. We are improving infrastructure such that even if a small clinic finds something, they can quickly connect to a lab or center that offers these investigations. The goal is to ensure seamless coordination between primary dental clinics and diagnostic centers so that regardless of where a patient presents, rural or urban, they can access timely, accurate, and comprehensive diagnostic care.

Dr. Akriti Mishra: Many oral conditions may look benign initially. How do oral pathologists distinguish between benign, pre-malignant, and malignant lesions?

Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal : You're absolutely right that many oral lesions can appear clinically harmless, which makes the role of an oral pathologist crucial in distinguishing between benign, pre-malignant, and malignant conditions. This distinction is primarily achieved through histopathological examination of biopsy tissue, supported by clinical context.

When we receive a biopsy, what we do is study the cells and tissue architecture under the microscope. Each category of lesion, whether benign, pre-malignant (dysplastic), or malignant, has characteristic features:

Benign lesions: These might be things like fibromas (overgrowths of fibrous tissue), benign ulcers from trauma, or hyperkeratosis (thickened keratin from irritation). Microscopically, benign lesions do not show the cellular abnormalities that cancers do. For instance, if a white patch is due to friction or irritation, the biopsy might just show a thickened layer of keratin and maybe some inflammation underneath, but the basal cells will appear normal and orderly. There will be no invasion into deeper tissue. In short, the cells look normal and well-differentiated, just maybe extra in number or thickness. As pathologists, we confirm a lesion is benign by noting the absence of dysplasia (no significant nuclear enlargement or irregularities, etc.).

Pre-malignant lesions (oral epithelial dysplasia): These are tricky because the tissue is not cancer yet, but it’s no longer normal. We look for features of dysplasia, which means abnormal development of the cells in the epithelium. Under the microscope, dysplastic cells might have larger, darker nuclei, higher DNA content, odd shapes, and they may be in places they shouldn’t (for example, dividing cells seen near the surface layer when normally they only divide in the basal layer). We also assess the architecture: is the layering of the epithelium disorganized? Are there drops of epithelial cells going downward (bulbous rete pegs) that hint at early invasion? We have grading for dysplasia (mild, moderate, severe) depending on how extensive these changes are in the epithelium. A pre-malignant lesion is basically contained to the epithelium (it hasn’t broken through the basement membrane), but the cells bear some hallmarks of malignancy. A classic example is a leukoplakia with dysplasia. Clinically it might look like a flat white patch, but on histology we might see, say, moderate dysplasia, which means if left unchecked, there’s a significant risk it could progress to cancer. It’s important to note that clinically, you cannot reliably distinguish a benign leukoplakia from one with dysplasia just by appearance. Studies show even innocent-looking homogeneous white patches can have dysplasia on biopsy. In fact, about 20% of leukoplakias show dysplasia or even early cancer on first biopsy, and certain high-risk sites like the tongue or floor of mouth show dysplasia in a much higher percentage. This is why we emphasize biopsies. The histopathology is more indicative of premalignant change than any clinical guesswork.

Malignant lesions (oral squamous cell carcinoma and others): When a lesion has become cancerous, microscopically we will see evidence of invasion. For squamous cell carcinoma (the most common oral cancer), that means the epithelial cells have broken through the basement membrane and are infiltrating into the underlying connective tissue. We often see irregular islands or cords of malignant squamous cells deep in the tissue where they don’t belong. The cells themselves show clear malignancy features: very large or irregular nuclei, high mitotic activity (lots of cell divisions, sometimes with abnormal mitotic figures), cells varying in size and shape (pleomorphism), and sometimes loss of the normal maturation pattern of squamous cells. In well-differentiated cancers, we might still see some keratin “pearls” or flattened cells, but in poorly differentiated ones the cells are very immature and bizarre-looking. Essentially, malignant pathology is confirmed by both the cellular atypia and the fact that the cancer cells are invading surrounding tissues. We also check margins of the biopsy to see if it’s likely all removed or not, and sometimes lymphovascular invasion, etc., which are more details for prognosis.

To summarize the process: an oral pathologist uses biopsy analysis to tell these apart. We correlate this with clinical presentation as well, for example, if a lesion was rapidly growing and ulcerated, we are on high alert for malignancy in the histology; whereas if it was a longstanding smooth white patch, we are looking carefully for dysplasia. Sometimes we use special stains or immunohistochemistry if needed. But generally, the H&E stained slide (the routine stain) is enough to make the call in most cases.

It’s important to note how critical this distinction is: Many lesions look benign to the patient (and even to the doctor), like a common white patch or a little lump, but only the pathology exam can reveal if there are early cancerous changes. For instance, as I mentioned, a homogeneous leukoplakia might just be thick keratin (benign) or might already harbor carcinoma in-situ. There’s no reliable way to tell just by looking in many cases (aside from some clinical red flags like a mixed red-and-white velvety texture, which tends to correlate with higher risk). That’s why, as an oral pathologist, I often say: when in doubt, do a biopsy. Our training also helps us guide clinicians on where to biopsy (since some lesions have areas that are worse than others). And if multiple lesions are present, we biopsy the one that looks most suspicious (e.g., the reddest or the one with the most induration).

In addition to standard microscopy, there are a few other tools: We sometimes use a microscope attachment to measure dysplasia objectively or emerging techniques like molecular assays to see if a lesion expresses certain markers associated with malignancy. But those are adjuncts and the fundamental method is still a thorough histological examination.

In conclusion, oral pathologists distinguish lesion nature by analyzing cellular details. A benign lesion will have a normal cell appearance and no invasion, a premalignant lesion will show internal warnings (atypia confined to epithelium, which is essentially a “warning shot”), and a malignant lesion will exhibit outright cancer features with invasion into tissues. It’s a meticulous process and often requires significant expertise to interpret subtle differences. This is the very reason we stress not to rely purely on visual examination in the mouth because a lesion that “looks harmless” could be in a dangerous early stage, and only our pathological analysis can uncover that hidden truth.

Dr. Akriti Mishra: Considering the large number of potential risk-factors in India (tobacco use, betel nut chewing, etc.), what preventive measures do you think are most effective for reducing oral cancer incidence?

Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal : When it comes to preventing oral cancer in India, the most effective strategies directly address its major risk factors. The chief factors among them include tobacco and areca nut (betel nut) use, often consumed together in the form of paan or gutkha, along with heavy alcohol intake. Eliminating or substantially reducing these habits is the single most impactful preventive measure.

Let me outline the key measures:

Tobacco Cessation (Smoking and Smokeless): Quitting tobacco is number one. Any form of tobacco, whether it’s cigarettes, bidis, chewing tobacco, gutkha, khaini, is harmful. Tobacco is by far the largest risk factor for oral cancer. We find that the vast majority of oral cancer patients (over 90%) have a history of tobacco use or heavy alcohol use. So, if we can get people to stop using tobacco, we will prevent a huge number of cases. This involves public health efforts to provide accessible cessation programs (like counseling, nicotine replacement therapies), and strong enforcement of tobacco control laws (like bans on gutkha, high taxation on tobacco products, and smoke-free public places). India has laws and warnings, for example, pictorial warnings on tobacco packs and banning flavored chewing tobacco, which need to be rigorously implemented. But beyond that, creating a culture where tobacco use is discouraged (similar to how smoking has become less socially acceptable over time) is important. In short: no tobacco = drastic reduction in oral cancer.

Areca Nut (Betel Quid) Cessation: Areca nut, often combined with betel leaf and sometimes tobacco, is a known cause of oral submucous fibrosis and contributes to oral cancer. Many people chew paan thinking it’s “herbal” or harmless, especially if without tobacco, but areca nut itself is carcinogenic. So, public awareness that even supari (plain betel nut) chewing is dangerous is needed. Preventive measure: discourage betel nut chewing by education and possibly regulation. For instance, some states have banned gutkha(which includes areca and tobacco together). We need to make sure those bans stay in effect and are enforced. Also, we should target youth because many start chewing pan masala or gutkha in their teens. Prevention programs in schools and colleges about the dangers of these products can be effective. Essentially, spitting out the paan habit will cut down a significant risk factor unique to our region.

Reduce Alcohol Consumption: Alcohol by itself is a risk factor and it synergistically increases the effect of tobacco. Someone who both drinks and uses tobacco has a multiplicative risk of oral cancer. So from a prevention point of view, moderating alcohol intake (especially hard spirits and in heavy quantities) is advised. The message isn’t as prominent in oral cancer campaigns as tobacco, but it’s important. Communities need education that heavy drinking, particularly with smoking or chewing, can markedly raise cancer risk. On a policy level, controlling alcohol availability and discouraging binge drinking are general public health measures that indirectly help cancer prevention too.

Diet and Nutrition: A diet rich in fruits and vegetables has been shown to have a protective effect against many cancers, including oral cancer. In India, there can be nutritional deficiencies in lower socioeconomic groups (for example, low intake of vitamin A, iron, etc., which can affect mucosal health). While diet alone won’t override the effects of tobacco, a healthy diet supports better immune function and mucosal repair. So, promoting consumption of fresh fruits, vegetables, and a balanced diet is a supportive preventive measure. It’s effective in the sense that it improves overall health and perhaps lowers cancer susceptibility a bit. Also, staying hydrated and maintaining good oral hygiene can help the oral tissues remain healthier (poor oral hygiene can lead to chronic irritation, which is a minor risk factor).

Avoidance of Other Carcinogens: This includes avoiding excessive sun exposure for the lips (lip cancer can be related to UV in farmers, etc., so using lip balms with SPF or wide-brim hats could be a simple preventive tip for outdoor workers) and avoiding exposure to HPV (Human Papillomavirus). HPV is a rising risk factor for oropharyngeal cancers. While not as common in oral cavity cancers in India yet, the HPV-related throat cancers are increasing. The preventive measure is vaccination. The HPV vaccine (traditionally aimed at cervical cancer prevention) can also eventually reduce oropharyngeal cancers. So, I’d advocate for HPV vaccination in the population as a supportive measure. Safe sexual practices and awareness about HPV is part of that prevention strategy too.

Regular Oral Screenings (Secondary Prevention): Aside from risk factor avoidance, another key preventive strategy is early detection through regular screenings. This is sometimes called secondary prevention, which means you’re preventing advanced disease by catching it early. We encourage people, especially those with known risks (like lifelong smokers or pan chewers), to get routine oral check-ups even if they have no symptoms. The idea is to spot any precancerous lesion when it can be managed. This has been effective in some community studies where high-risk individuals undergo periodic mouth exams as it leads to finding lesions and treating them before they become cancer. So, scaling up screening programs in communities (for example, incorporating an oral exam in general health camps, or using mobile dental clinics in villages) can effectively reduce the incidence of advanced oral cancers. It’s worth noting that screening doesn’t prevent the lesion from occurring, but it prevents it from progressing to a lethal stage by catching it early. So it’s a crucial part of the strategy in a high-risk country like ours.

Education and Myth-busting: A preventive measure often overlooked is simply public education to dispel myths. For instance, there is a misconception in some places that chewing tobacco or tobacco toothpaste is good for dental health, which is absolutely untrue and propagated by certain product marketing in the past. Educating people that these practices are dangerous is prevention. Also, making people aware that oral cancer is preventable and treatable if caught early can motivate them to give up habits and go for check-ups. Often, lower socio-economic populations might think “fate” or “karma” causes cancer, or they might use traditional remedies for mouth lesions. We have to reach out in culturally appropriate ways to change those perceptions.

To summarize, the most effective preventive measures are those targeting tobacco and areca nut use. Thus, basically stopping the cause at its source. This yields the largest benefit. Supporting measures like alcohol moderation, nutritious diet, good oral hygiene, and regular screenings come next. India has started large anti-tobacco campaigns (you might have seen the graphic warnings and public service ads with oral cancer patients, which have been impactful). We need to continue and strengthen these. If we imagine a future where chewing gutkha or smoking becomes a rarity, we will have dramatically fewer cases of oral cancer. It’s a tough battle because of addiction and social norms, but that’s where the focus lies for prevention.

In this part, Dr. Bhuvan Nagpal outlines the importance of diagnostic and preventive approaches in reducing the oral cancer burden, emphasizing the role of timely identification and risk-based intervention. In Part 4, he broadens the discussion to public outreach, highlighting how community awareness efforts and digital platforms can transform oral cancer education, improve patient engagement, and encourage earlier help-seeking behavior.