Beyond hormonal management, Estes says an exercise regimen and weight loss are often effective.

After her diagnosis, Sridhar was prescribed Metformin, a diabetes drug often used to treat PCOS, but the side effects were too intense, and she had to stop taking it. Her condition continued to worsen as she completed medical school and moved into residency, where she was encouraged to lose weight. Despite her best efforts, the weight refused to budge.

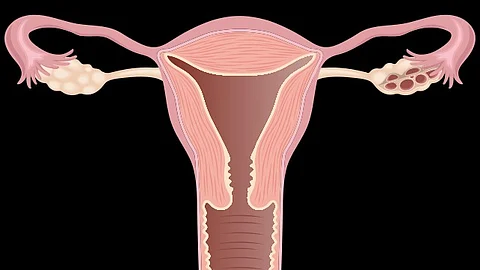

As she started her fellowship at Penn State College of Medicine, she turned to Legro and Estes for help and found that, in addition to PCOS, she had precancerous lesions in her uterus.

To fast-track her treatment, she asked to try GLP-1 agonists, a medication used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity, and finally found the results she needed.

While weight loss can help diminish symptoms of PCOS, Legro is careful to point out that the disorder is not directly caused by higher body weight.