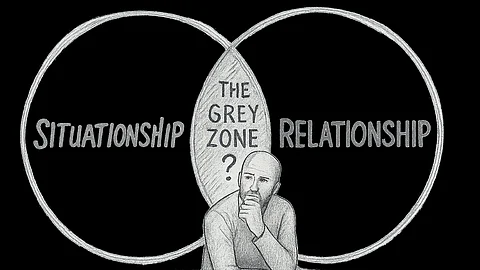

A situationship is defined by the absence of formal labels. People involved often describe themselves as “just talking” or “seeing each other,” carefully avoiding the definitive step of calling it a relationship. Expectations remain fluid—partners tend to shy away from conversations about exclusivity, future planning, or shared responsibilities. Commitment, if it exists, is sporadic and dictated more by convenience than by intentional effort. For some, this flexibility offers freedom, but for many, it lays the groundwork for emotional instability.

Psychologically, the lack of clarity fuels anxiety and uncertainty. Ambiguity creates a mental tug-of-war: one partner may crave reassurance and long for consistency, while the other resists any form of definition. For individuals with an anxious attachment style, this can be especially damaging. They seek security but rarely receive it in a situationship, leading to emotional exhaustion. The imbalance is often glaring—while one partner invests time, emotions, and hopes for progression, the other remains comfortably detached under the guise of “keeping it casual.” This unequal investment generates a subtle but powerful power asymmetry.

From a neurological perspective, situationships mimic addictive behaviour. Neuroscience research shows that dopamine—the brain’s “reward chemical”—spikes during moments of affection or intimacy. But when affection is inconsistent and unpredictable, the reward system works much like gambling. In slot machines, players keep pulling the lever because the next spin might deliver a reward. Similarly, in a situationship, the partner receiving intermittent affection remains hooked because “the next interaction might mean more.” This cycle reinforces attachment even when satisfaction remains chronically low.

The dynamic has clear real-world parallels. Think of the friend who only texts when they’re bored, or the partner who carefully avoids defining “what this is.” These patterns keep one person perpetually on edge, anxious about where they stand, while the other maintains control by withholding clarity. Over time, this leaves the emotionally invested partner trapped in a cycle of hope and disappointment, making the exit from such entanglements even harder.