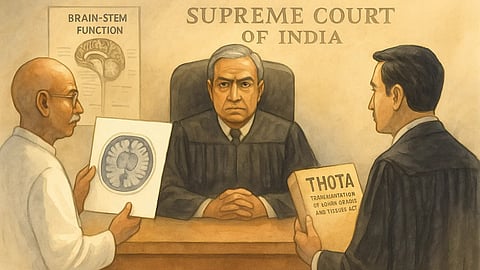

Dr. Ganapathy’s View:

Dr. Ganapathy maintains that declaring a person "brain dead", even while physiological functions continue, amounts to harvesting organs from live bodies and infringes on constitutional protections.

It was pointed out by Dr. Ganapathy that there is no uniform assessment in regard to brain death across the globe. According to him, in the US, brain death is certified when the whole brain has come to irreversible cessation, and it is required to declare a patient suffering from brain death by observing 24 hours. He points out that whereas in the UK it is not necessary that the whole brain has to come to an irreversible cessation, and it is sufficient that observations are made for 6 hours. It is sufficient in the UK that all functions of the brain stem irreversibly cease to function. In India, brain death is certified when all the functions of the brain stem have permanently and irreversibly ceased (Section 2(d) of THOTA) and it is sufficient that observations are made for 6 hours.