WWII camp experiments in Germany targeted three main areas: survival of military personnel, evaluation of medications and therapies, and promotion of racial pseudoscience and ideological goals.

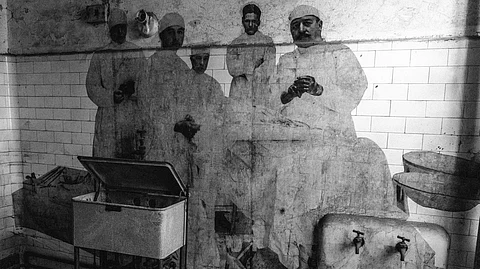

These unethical medical research practices were conducted without consent and using inhumane methods. [2]

They included:

1. Hypothermia and High-Altitude Experiments

At Dachau concentration camp, victims were immersed in ice water (2–12°C) to study Nazi hypothermia experiments.

Some rewarming involved immersion in very hot or near-scalding water, sometimes described as “boiling” in testimonies.

Subjects were clothed or naked, conscious or anesthetized. Out of 280 to 300 victims in over 360 to 400 experiments, 80–90 died; only two survived the war, both with severe mental deficits. [3]

Sigmund Rascher, the lead investigator, also conducted Nazi high-altitude experiments using low-pressure cabins.

With the effects of high altitude and hypothermia, like mental disturbances, decreased oxygen, and irregular heartbeats, the victims would have experienced excruciating pain before death. [4]