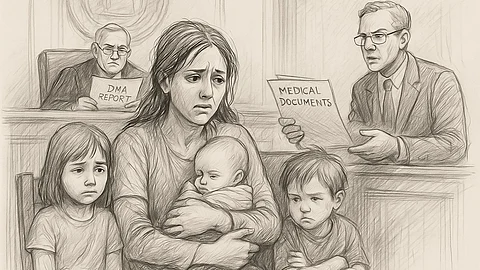

Karen, like Lydia, had given birth to all three of her children. So how could there be no DNA match? The hospital then tested her third son—his DNA matched hers. Confused and alarmed, the doctors proceeded with the transplant using her husband as the donor, since only he was a compatible donor. The surgery was successful.

Curious about the unusual DNA results, the medical team dug deeper. They hypothesized that Karen might have a rare genetic condition. They tested samples from her blood, cheek swabs, and hair—but none matched her first two sons. Then they remembered a sample from a thyroid surgery she had years earlier. They retrieved it from the pathology lab and tested it—and this time, the DNA was a match with her first two sons.

Karen Keegan was diagnosed with Chimerism, a rare condition in which a person carries two distinct sets of DNA.