No team of specialists. No lab tests. No ECG machines that beeped warnings.

Just her stethoscope. A sphygmomanometer. And a little bottle of Sarpagandha.

That was 1938. Sevagram.

Each morning, she checked his pressure. Each evening, she logged the numbers. The readings danced—down, then up, then up again. She adjusted the dose. Changed his diet. Watched him closely.

He cooperated. He joked. He listened. He let her take charge.

But his blood pressure refused to behave.

It didn’t make sense.

He was lean—46 kilos. His waist was slim. Ate no meat. Used no tobacco. No alcohol. Took salt like medicine—in pinches. Walked 18 kilometers a day. Slept early. Rose before dawn. Practised yoga, mud therapy. Laughed. Meditated. Lived as simply as a sage.

And yet—his blood pressure soared.

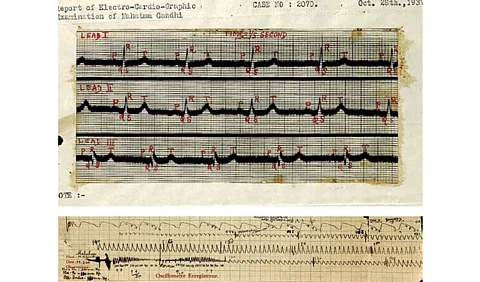

No signs of heart disease. His ECG in 1939? Normal. Just three leads, but still—no arrhythmia, no strain.

What was the cause?

Stress? Genetics? The burden of leading a nation? No one could tell.

And here’s the twist.

Despite those wild readings, Gandhi showed no symptoms. No stroke. No heart attack. No kidney failure.

Would he have lived to 125, as he once hoped?

We’ll never know. His journey ended with a bullet in 1948.

But what remains is this—

Not that he had high blood pressure.

But that he placed his faith in a young intern.

That he allowed her—not a famous cardiologist—to hold the stethoscope to his chest.

And that faith made all the difference.

Courtesy: Dr. SP Kalantri from his website (https://sp.kalantri.co.in)

About the author:

Dr. SP Kalantri, MD, MPH, is Director Professor of Medicine at Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (MGIMS) and Medical Superintendent of Kasturba Hospital. A physician, educator, and public health expert, he earned his MD in 1981 and later completed an MPH in Epidemiology from the University of California, Berkeley. At MGIMS, he leads clinical services, trains future doctors, and conducts impactful research.