The NETs stop UTIs from spreading and wreaking havoc elsewhere in the urinary tract.

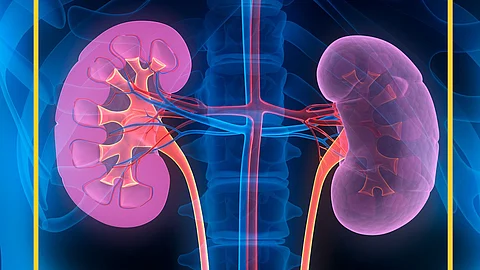

Indeed, bacterial invasion of the lower urinary tract is common, according to the World Health Organization, which estimates that hundreds of millions of people are impacted globally each year. Usually, UTIs are limited to the bladder on rare occasions, the invading microbes defy the body's immunological defenses by migrating up the urinary tract and into one or both the kidneys.

Once infected, the kidneys are susceptible to serious complications. The body has antimicrobial strategies, NETosis helps confine bacteria to the bladder, keeping the kidneys infection-free.

"Lower UTI is common but is rarely complicated by pyelonephritis," Stewart added. Pyelonephritis refers to an infection in one or both kidneys. The condition, which is marked by pain and potent inflammation, requires immediate medical care, doctors say because, in some instances, pyelonephritis can be life-threatening.

The Cambridge team analyzed urine samples from 15 healthy people. The scientists found that one biological entity stood out—the presence of NETs. These structures interacted with a protein called uromodulin, which aided in the formation of large webs that entrapped disease-causing bacteria.

The authors validated these findings in mouse models of UTI caused by E. coli. Stewart and colleagues found that interrupting NET formation allowed bacteria to invade the kidneys.

"We identified neutrophil extracellular traps in healthy human urine that provide an antibacterial defense strategy within the urinary tract," Stewart asserted.